From the creative sovereignty of the ‘Brother’ generation to the global standardization of algorithms: a strategic reflection on the alienation of the writer, the passive consumption of “average content,” and the ethical challenge of Artificial Intelligence versus human authenticity.

By Edinson Martínez

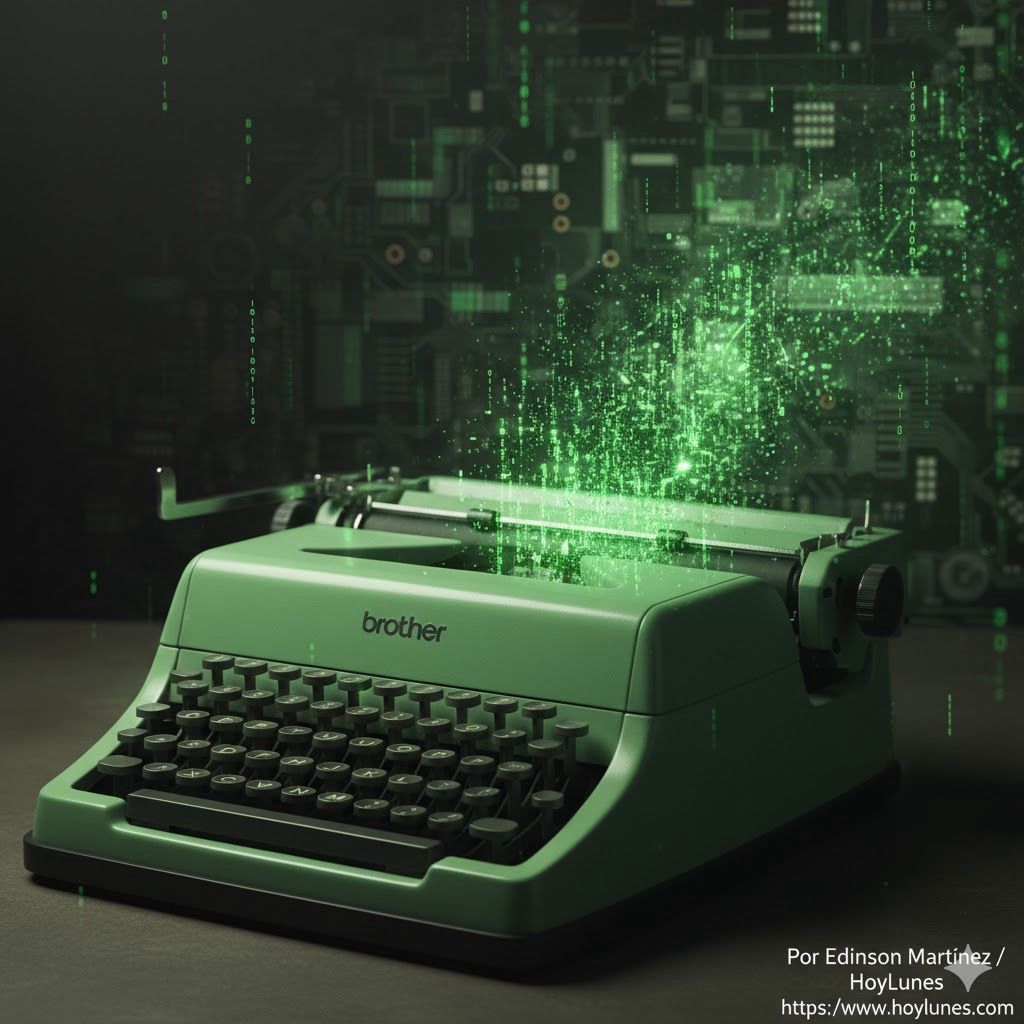

HoyLunes – When I began writing my first articles, a little more than half a century ago, I did so on a Brother typewriter. This was common among the youth of my generation; that machine had already passed through several hands because it was the most modern tool available at the time. The texts revolved around themes as elementary as they were naive, drawn from our immediate surroundings. As the history of the latter half of the 20th century records, the intellectual climate of the era was heavily influenced by the authors of the Latin American literary “boom” and a wealth of political literature.

Those were the times of a restless youth who wrote about whatever they wished, with no restrictions other than those derived from their own particular perception—much as I understand was the case for established authors and anyone aspiring to forge a place for themselves in the world of letters. Thus, freedom—or, in any case, the sovereignty to choose the topics one wrote about—was a matter solely at the discretion and decision of the author. Perhaps a thoughtful hint, a timid suggestion, or a recommendation from one’s inner circle was permitted to shade or influence the presentation of certain ideas, but never an imposition from third parties for reasons of style or market trends, which would alienate the natural sovereignty of the craft of writing.

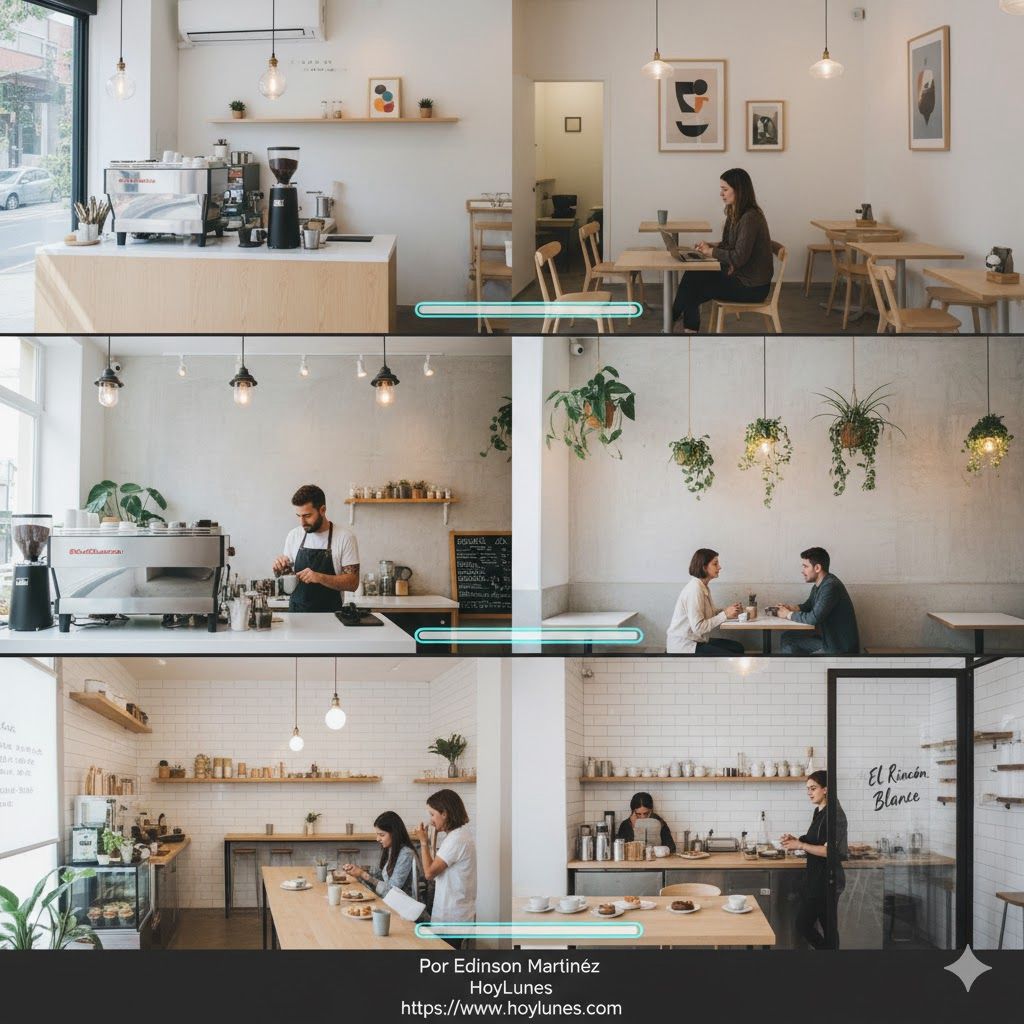

The title I chose for these notes has been used by other authors before to describe the same purpose that drives this piece. One of them is “Kyle Chayka”[1], in his article ´The Tyranny of the Algorithm: Why Every Coffee Shop Looks the Same´, where he develops a well-argued exposition on the influence algorithms exert over people’s preferences. Although the issue is not truly new—since in the past the influence of the mass media was decisive in the manipulation of collective consciousness on a global scale—the writing in question poses a disturbing line of argument regarding collective alienation in the present century: a reality of stereotypes and similar perspectives such as humanity has never known before, where the cornerstone of this entire process is the overwhelming influence of social networks.

If in the past the manufacturing of stereotypes was a process of permanent cultural reproduction, it occurred over relatively long periods of time that allowed for a rebellious social reaction. To this, one must add an intellectual context endowed with cultural values capable of containing, with a critical sense, the intent to standardize tastes and the very conception of life. Hence the abundant literature on the subject during that period. From that era, it is worth citing, for example, the work of “Wilson Bryan Key” (1988), ´Subliminal Seduction´:

“Subliminal languages are not taught in schools: the basis of the effectiveness of modern media is a language within a language, one that communicates to each of us at a level below our conscious knowledge, reaching the unknown mechanism of the human unconscious. This is a language based on the human capacity to receive subliminal, subconscious, or unconscious information. This language has truly produced the profit base of the mass media.” (p. 39).

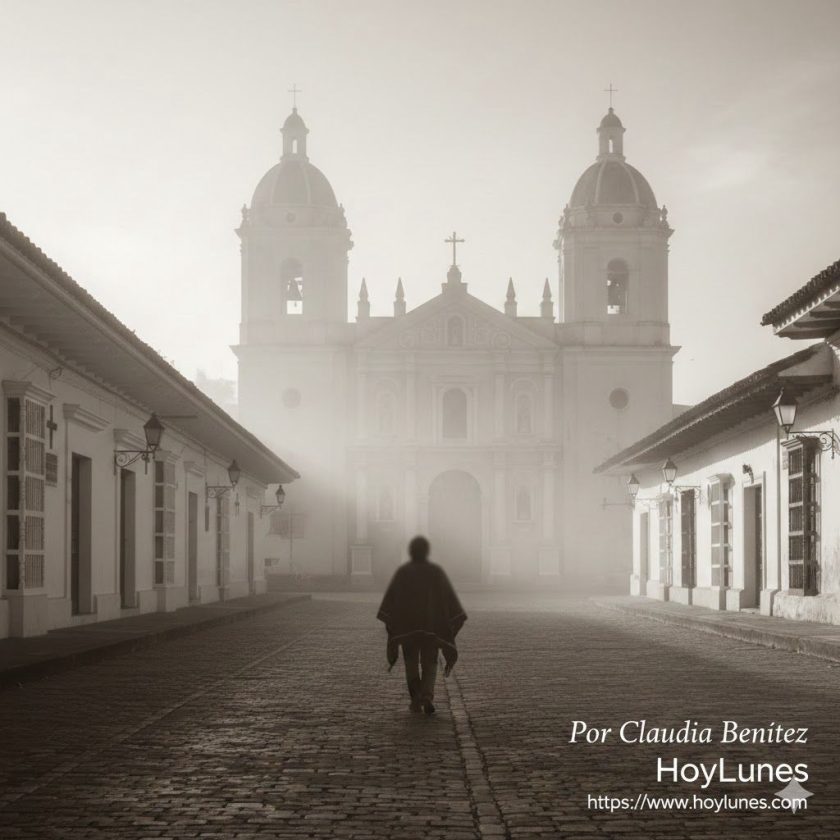

Today, looking at the last twenty years, that context of stereotype reproduction has intensified dramatically. What once took months or days to consolidate is now achieved in instants. Thus, an idea, image, or statement can travel the world immediately and, thanks to algorithms, its impact can be known almost instantly. Chayka’s article describes how it no longer matters if you are in Bogotá, Madrid, or Tokyo; the algorithm has dictated a global aesthetic standard that nullifies local identity in favor of a uniformity of tastes. He explains how businesses have adopted identical aesthetics so that they all share the same image. One might ask: “What is wrong with that?” In appearance, nothing, if valued only as an aesthetic trend. The matter becomes complicated when that same algorithm imposes preferences in other areas, such as politics, where we already see the reclamation of past perversions while civilizational achievements are cast aside if it suits certain global interests.

This is where my reflection on literature fits. I believe that never in history have there been so many people writing and so many readers converging on two sides of the same coin. My fear is that this marvel of human ingenuity will end up being a commodity in the strictest sense; that the intellectual exercise will conclude by telling readers only what they want according to previously stereotyped preferences, in a clear alienation of their intellectual sovereignty. This would be an abominable drift that would banish the brilliance of authenticity from creation.

We would have, on one hand, a legion of consumers of “average content” dictated by massive platforms and, on the other, pseudo-literature usurping the place of authentic creation. This is a reality difficult to unveil when the mask of post-truth dominates society, making “Herbert Marcuse’s” warning a reality: “The real catastrophe is the prospect of total idiotization, dehumanization, and manipulation of man”.

In this context, I fear that the role of writers will be compromised by the presence of AI as an instrument to generate content that feeds mass consumption, in accordance with the artless writing of the algorithm. We are facing a double alienation: the writer loses control over their creativity—no longer deciding genre, style, or theme—and the reader consumes what reaches them under a veiled manipulation. I am overwhelmed by the idea of literature transforming into a fashion product, when in reality it is a testimony of life. When we read Saramago, Rulfo, Borges, or García Márquez, we connect with the obsessions, the fears, and the time that envelops the authors—the dry and spectral landscape as the residue of a revolution, for example; the cosmogony that changed the perception of Latin American literature; or the Buenos Aires labyrinths of a city that remains forever in the reader’s imagination.

Literature is the most transcendent human creation since the invention of writing and, perhaps, the most relevant intellectual prodigy since the very moment our ancestors felt the weight of their being upon seeing their face reflected in a stream.

The danger is not that AI writes like a genius or is capable of imitating our emotions, but that human beings become accustomed to reading like machines, trapped in the average content of social networks without acknowledging exceptionality—that wonder with which each author presents themselves to their readers, the ´élan vital´ that drives them to conceive literature as a constant challenge of their abilities to surprise their fellow humans. Humanity has never faced this risk before, even when in the past the mass media openly influenced currents of opinion, fashions, and consumption preferences.

I am not sure that, with the staggering deployment of new technologies and platforms, we can have a balanced coexistence between them and the art of writing. Ideally, they should serve primarily as support instruments—whether for documentation or immediacy in accessing sources—and not as a replacement for human ingenuity, turning us into victims of the statistical probability dictated by algorithms. It is a struggle of unpredictable results that may ultimately favor the perspective I represent; it is possible, given the history built by man, but no one could guarantee it.

Some with whom I have discussed the subject bring up the case of photography: when it appeared, painters—including portraitists—imagined their art would disappear, but over time photography also evolved into an art form. I am not sure the same will happen in our time in the inevitable interaction between writers, readers, AI, and social networks.

For now, those of us who desire a sovereign assessment of the matter can only persist. Let us seek a way in which a technology that threatens to “wipe the slate clean” ends up facilitating things so that, like the sculptor, the AI limits itself to finding the stone in the quarry, cutting and polishing it, so that the artist finally carves it and creates the work to be admired as an expression of their authentic exceptionality, and not as the boring routine of a stereotype that surprises no one.

[1] Kyle Chayka is a renowned American journalist and cultural critic, currently a staff writer at The New Yorker, where he writes the “Infinite Scroll” column on technology and internet culture.

`#FreeLiterature` `#TyrannyOfTheAlgorithm` `#ArtificialIntelligence` `#IntellectualSovereignty` `#CriticalThinking` `#CreativeWriting` `#DigitalHumanism` `#EdinsonMartínez` `#HoyLunes`